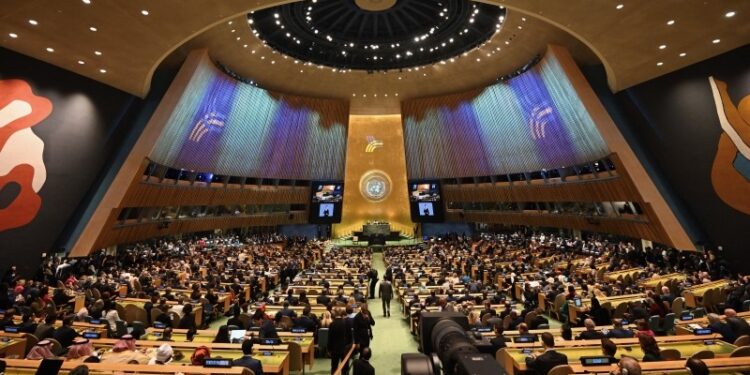

On 25 October 2025, sixty five nations gathered in Hanoi, Vietnam, to sign the United Nations Convention on Cybercrime. It is the world’s first global framework to tackle crimes committed through information and communication technologies. UN Secretary General António Guterres called it “a historic step toward a safer digital world.” But in truth, the signing was the easy part. The real test lies in what comes next.

The treaty, adopted by the UN General Assembly late last year after five long years of negotiation, sets out how countries can work together to investigate and prosecute cyber dependent and cyber enabled crimes. It makes clear that offences such as ransomware, data interference, and the non consensual sharing of intimate images are not just personal violations but crimes that demand accountability. It also introduces 24 hour cooperation points for evidence sharing across borders and, crucially, insists that privacy and freedom of expression must not be traded away in the name of security.

That balance between protection and rights is delicate. As Guterres reminded delegates in Hanoi, technology has brought progress, but also peril. “Every day, sophisticated scams defraud families, steal livelihoods, and drain billions from our economies,” he said. “In cyberspace, nobody is safe until everybody is safe.”

For Southern Africa, this treaty lands at a defining moment. The region is steadily digitising, yet its defences remain patchy. South Africa, Zimbabwe, and Namibia have taken strides with new cybercrime and data protection laws, but many other states are still catching up. The Convention offers something rare: a chance to build unity around a common standard for fighting digital crime.

Zimbabwe’s delegation, led by the Minister of ICT, Postal and Courier Services, Honourable Tatenda Mavetera, signed the Convention with an eye on consolidation. The Data Protection Act and the Computer Crime and Cybercrime Act, both from 2021, gave the country a starting point. The National Cybersecurity Strategy of 2025 now adds structure, and the partnership with Cyberus Technology shows intent to pair regulation with skill building. It is an encouraging shift from simply passing laws to actually enforcing them through trained people and functional systems.

Still, the gaps remain wide. Many countries in the Southern African Development Community lack digital forensic tools and the expertise to trace or preserve electronic evidence. Legal definitions vary, prosecutors lag behind the speed of digital investigations, and cross border collaboration is bogged down by paperwork and politics. Without deliberate regional planning and money on the table, the Convention risks becoming another fine global idea that falters at home.

The Budapest Convention of 2001 offers a cautionary tale. It pioneered international cooperation on cybercrime but left many African states feeling like outsiders. It spoke more for Europe than for the world. The new UN Convention is meant to fix that by being inclusive from the start. But inclusivity will mean little if it is not backed by capacity and implementation on the ground.

To make this work, Southern Africa needs three clear priorities. First, build capacity. Cybersecurity and digital forensics should not depend on donor projects or workshops; they must be part of the region’s own academic and institutional frameworks. Second, integrate regionally. SADC must move beyond declarations and set up a functional cooperation framework to share intelligence and harmonise laws. Third, protect rights. Digital enforcement cannot become an excuse to snoop, silence, or intimidate citizens. The same rights we fight to protect offline must hold firm online.

When Guterres closed the ceremony, he issued a reminder that could easily serve as a warning: “Now we must turn signatures into action.” For developing countries, he said, implementation will require not only political will but also funding, training, and technology.

That is the heart of the matter. Signing the treaty earns applause; enforcing it earns trust. Southern Africa has signed up to a vision of shared security, but the region’s safety will depend on how much of that vision survives beyond the speeches.

If governments can follow through with genuine cooperation and respect for human rights, then perhaps history will remember 25 October 2025 not as the day the world talked about cyber safety, but as the day it started building it.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial stance of this publication.

About the Author: Kundai Darlington Vambe (LLB, University of London) is a Zimbabwean law expert and commentator who writes on law, governance, and technology, with a focus on artificial intelligence and cybercrime policy in Southern Africa.